GKS 2232 4º: Guaman Poma, Nueva corónica y buen

gobierno (1615)

-

Title page

-

1. The first new chronicle (1-13)

-

2. “How God ordained the writing of this book” (14-21)

-

3. The chapter of the ages of the world (22-32)

-

4. The chapter of the popes and their reigns (33-47)

-

5. The chapter of the ages of the Indians (48-78)

-

6. The chapter of the Inkas (79-119)

-

The first coat of arms of the Inka (p. 79)

-

The second coat of arms of the Inka (p. 83)

-

The first Inka, Manco Capac Inka (p. 86)

-

The second Inka, Sinchi Roca Inka (p. 88)

-

The birth of Jesus Christ in Bethlehem (p. 90) (See also p. 30.)

-

Saint Bartholomew in the province of Collao (p. 92)

-

The third Inka, Lloque Yupanqui Inka (p. 96)

-

The fourth Inka, Mayta Capac Inka (p. 98)

-

The fifth Inka, Capac Yupanqui Inka (p. 100)

-

The sixth Inka, Inka Roca, with his son (p. 102)

-

The seventh Inka, Yahuar Huaca Inka (p. 104)

-

The eighth Inka, Viracocha Inka (p. 106)

-

The ninth Inka, Pachacuti Inka (p. 108)

-

The tenth Inka, Tupac Inka Yupanqui (p. 110)

-

The eleventh Inka, Huayna Capac Inka (p. 112)

-

The twelfth Inka, Tupac Cuci Hualpa Huascar Inka (p. 115)

-

7. The chapter of the queens, or quya (120-144)

-

The first quya, Mama Huaco (p. 120)

-

The second quya, Chinbo Urma (p. 122)

-

The third quya, Mama Cora Ocllo (p. 124)

-

The fourth quya, Chinbo Urma Mama Yachi (p. 126)

-

The fifth quya, Chinbo Ucllo Mama Caua (p. 128)

-

The sixth quya, Cuci Chinbo Mama Micay (p. 130)

-

The seventh quya, Ipa Huaco Mama Machi (p. 132)

-

The eighth quya, Mama Yunto Cayan (p. 134)

-

The ninth quya, Mama Ana Uarque (p. 136)

-

The tenth quya, Mama Ocllo (p. 138)

-

The eleventh quya, Raua Ocllo (p. 140)

-

The twelfth quya, Chuqui Llanto (p. 142)

-

8. The chapter of the Inka’s captains and their noble ladies (145-183)

-

The first captain, Inka Yupanqui (p. 145)

-

The second captain, Tupac Amaru Inka (p. 147)

-

The third captain, Cuci Uanan Chiri Inka (p. 149)

-

The fourth captain, Maytac Inka, apu (p. 151)

-

The fifth captain, Auqui Tupac Inka Yupanqui (p. 153)

-

The sixth captain, Otorongo Achachi Inka, or Camac Inka, apu (p. 155)

-

The seventh captain, Maytac Inka (p. 157)

-

The eighth captain, Camac Inka, apu (p. 159)

-

The ninth captain, Urcon Inka (p. 161)

-

The tenth captain, Challco Chima Inka (p. 163)

-

The eleventh captain, Rumiñavi (p. 165)

-

The twelfth captain, Guaman Chaua, qhapaq apu, powerful lord (p. 167)

-

The thirteenth captain, Ninarua, qhapaq apu, powerful lord (p. 169)

-

The fourteenth captain, Mallco Castilla Pari (p. 171)

-

The fifteenth captain, Malco Mullo (p. 173)

-

The first queen and lady, Poma Ualca, qhapaq warmi, powerful lady (p. 175)

-

The second lady, Mallquima, qhapaq, powerful (p. 177)

-

The third lady, Umita Llama, qhapaq, powerful (p. 179)

-

The fourth lady, Mallco Guarmi Timtama (p. 181)

-

-

10. The chapter of the general inspection, or census (195-236)

-

The first "street" or age group of men, awqa kamayuq, warrior of thirty-three years (p. 196)

-

The second "street" or age group, puriq machu, the old man of sixty years who walks (p. 198)

-

The third "street" or age group, ruqt'u machu, the deaf old man of eighty years (p. 200)

-

The fourth "street" or age group, unquq runa, the sick man, of all ages (p. 202)

-

The fifth "street" or age group, sayapayaq, messenger of eighteen years (p. 204)

-

The sixth "street" or age group, maqt'a, youth of twelve years (p. 206)

-

The seventh "street" or age group, t'uqllakuq wamra, boy hunter of nine years (p. 208)

-

The eighth "street" or age group, pukllakuq, playful little boy of five years (p. 210)

-

The ninth "street" or age group, llullu wamra, tender child of one year (p. 212)

-

The tenth "street" or age group, k'irawpi kaq, one-month-old babe in cradle (p. 214)

-

The first "street" or age group of women, awakuq warmi, weaver of thirty-three years (p. 217)

-

The second “street” or age group, payakuna, old woman of fifty years (p. 219)

-

The third “street” or age group, puñuq paya, sleepy old woman of eighty years (p. 221)

-

The fourth “street” or age group, unquq k’umu, sickly hunchbacks of all ages (p. 223)

-

The fifth “street” or age group, sipaskuna, virgin of thirty-three years (p. 225)

-

The sixth “street” or age group, qhuru thaski, short-haired girl of twelve years (p. 227)

-

The seventh “street” or age group, pawaw pallaq, girl of nine years who gathers flowers (p. 229)

-

The eighth “street” or age group, pukllakuq wamra, playful little girl of five years (p. 231)

-

The ninth “street” or age group, lluqhaq wamra, little girl who crawls, of one year (p. 233)

-

The tenth “street” or age group, k’irawpi kaq wawa, babe in crib, one month old (p. 235)

-

11. The chapter of the months of the year (237-262) (See also ch. 37.)

-

The first month, January; Qhapaq Raymi, the greatest feast; samay killa, month of rest (p. 238)

-

The second month, February; Pawqar Waray Killa, month of donning precious loincloths (p. 240)

-

The third month, March; Pacha Puquy Killa, month of the maturation of the soil (p. 242)

-

The fourth month, April; Inka Raymi, feast of the Inka; samay, rest (p. 244)

-

The fifth month, May; Hatun Kuski, great search; aymuray killa, month of harvest (p. 246)

-

The sixth month, June; Hawkay Kuski, rest from the harvest (p. 248)

-

The seventh month, July; Chakra rikuy chakra qunakuy chawa warkum killa, month of the inspection and distribution of lands (p. 250)

-

The eighth month, August; Chacra Yapuy Killa, month of turning the soil (p. 252)

-

The ninth month, September; Quya Raymi Killa, month of the feast of the queen, or quya (p. 254)

-

The tenth month, October; Uma Raymi Killa, month of the principal feast (p. 256)

-

The eleventh month, November; Aya Marq'ay Killa, month of carrying the dead (p. 258)

-

The twelfth month, December; Qhapaq Inti Raymi, month of the festivity of the lord sun (p. 260)

-

12. The chapter of the idols (263-288)

-

Divinities of the Inka, Waqa willka inkap (p. 263)

-

Idols of the Inkas: Inti, Uana Cauri, Tambo Toco, Pacari Tambo (p. 266)

-

Idols and waqas of the Chinchaysuyus in Paria Caca; Pacha Kamaq, creator of the universe (p. 268)

-

Idols and waqas of the Antisuyus, Saua Ciray, Pitu Ciray (p. 270)

-

Idols and waqas of the Qullasuyus, Uillca Nota (p. 272)

-

Idols and waqas of the Kuntisuyus, Coropona (p. 274)

-

High priests, walla wisa, layqha, umu, sorcerer (p. 279)

-

Llulla layqha umu, deceitful sorcerers and witches (p. 281)

-

Superstitions and omens: atitapya, bad omens; aquyraki, misfortunes (p. 283)

-

Processions, fasts, and penitence: waqaylli, sasikuy, and llakikuy (p. 286)

-

13. The chapter of burials (289-299)

-

14. The chapter of the Inka’s chosen virgins (300-303)

-

15. The chapter of the Inka’s justice (303-316)

-

16. The chapter of festivals (317-329)

-

17. The chapter of the Inka's patrimony (330-341)

-

18. The chapter of the Inka's government (342-369)

-

The Inka’s council: Inkap rantin qhapaq apu, the great lord who represents the Inka; Guaman Chaua, most excellent lord (p. 342)

-

The Inka’s council: Hanan Cuzco Inka, principal lord; qhapaq apu wataq, court magistrate who apprehends rebellious lords (p. 344)

-

Chief law enforcement official: Hurin Cuzco Inka; chaqnay kamayuq, torturer (p. 346)

-

Provincial administrator, t’uqriykuq, royal official (p. 348)

-

Provincial administrators, suyuyuq; sons of great lords, qhapaq apu (p. 350)

-

Couriers of greater and lesser rank: hatun chaski, chief courier; churu mullu chaski, the courier who carries a trumpet shell (p. 352)

-

Surveyers of this kingdom: Una Caucho Inka and Cona Raqui Inka (p. 354)

-

Governor of the royal roads, qhapaq ñan t’uqrikuq; the royal road, or qhapaq ñan, of Bilcas Guaman (p. 356)

-

Governor of the bridges of this kingdom, chaka suyuyuq (p. 358)

-

The Inka’s council: Inkap khipuqnin qhapaq apukunap kamachikuynin khipuq, the Inka’s secretary and accountant who records the dispositions of the royal lords (p. 360)

-

Chief accountant and treasurer, Tawantin Suyu khipuq kuraka, authority in charge of the knotted strings, or khipu, of the kingdom (p. 362)

-

Inspector of these kingdoms, taripakuq (p. 364)

-

Royal council of these kingdoms, Qhapaq Inka Tawantin Suyu kamachikuq apukuna, the Inka lords who govern Tawantinsuyu (p. 366)

-

Guaman Poma says, “But, tell me,” as he inquires about the history of ancient Peru. (p. 368)

-

19. The chapter of the Spanish conquest and the civil wars (370-437)

-

The Inka asks what the Spaniard eats. The Spaniard replies: “Gold.” (p. 371)

-

The conquistadors Don Diego de Almagro and Don Francisco Pizarro (p. 373)

-

The voyages of New World discovery and conquest: Christopher Columbus, Juan Díaz de Solís, Diego de Almagro, Francisco Pizarro, Vasco Núñez de Balboa, and Martín Fernández de Enciso. (p. 375) (See also p. 46.)

-

Don Martín de Ayala, the first ambassador of Huascar Inka and father of Guaman Poma, greets Don Francisco Pizarro and Don Diego de Almagro, ambassadors of the Spanish king. (p. 377)

-

The body of Huayna Capac Inka, being carried from Quito to Cuzco for burial (p. 379)

-

The Captain Rumiñavi, emissary of Atahualpa, presents Don Francisco Pizarro and Don Diego de Almagro with two maidens in order to convince the Spaniards to return to their homeland. (p. 381)

-

The conquistadors Sebastián de Balcázar (actually, Benalcázar) and Hernando Pizarro confront Atahualpa Inka at the royal baths of Cajamarca. (p. 384)

-

Don Diego de Almagro, Don Francisco Pizarro, and Friar Vicente de Valverde kneeling before Atahualpa Inka at Cajamarca, with the Indian Felipillo acting as interpreter (p.386)

-

Atahualpa Inka in his prison at Cajamarca (p.389)

-

The execution of Atahualpa Inka in Cajamarca: Umanta kuchun, they behead him. (p.392)

-

Captain Luis de Ávalos de Ayala kills Quizo Yupanqui Inka in the conquest of Lima. (p.394)

-

The style of dress worn by the first Spaniards in Peru (p.396)

-

Don Francisco Pizarro setting fire to the house of Guaman Poma’s grandfather: “Hand over your gold and silver!” (p.398)

-

The newly reigning Manco Inka in his ceremonial throne in Cuzco (p.400)

-

Manco Inka attempts to burn the Inka palace of Cuyus Mango, now a temple of Christian worship, but God intervenes and prevents its destruction. (p.402)

-

The miracle of Santa María de Peña de Francia: Inka soldiers are frightened in battle by the miraculous apparition and flee. (p.404)

-

St. James the Great, Apostle of Christ, intervenes in the war in Cuzco. (p.406)

-

The royal inspector Damián de la Bandera asks the mother of a young boy to identify her son. She responds, “He is the son of a powerful lord.” (p.410)

-

The death of Don Francisco Pizarro by the sword of Don Diego de Almagro, the mestizo son of Pizarro’s former ally (p.412)

-

Gonzalo Pizarro kills the mestizo rebel Don Diego de Almagro. (p.414)

-

Viceroy Blasco Núñez de Vela orders the execution of the conquistador Illán Suárez de Carvajal. (p.416)

-

King Charles V of Spain sends president Pedro de la Gasca to Peru with a letter requesting the loyalty of Gonzalo Pizarro and his soldiers. (p.419)

-

The solemn reception of Captain Francisco Carvajal in Lima by Gonzalo Pizarro and other city officials (p.421)

-

President Pedro de la Gasca forces Gonzalo Pizarro to flee in battle. (p.426)

-

President Pedro de la Gasca receives the priestly emissary sent by Gonzalo Pizarro and demands the rebel’s obedience to the king. (p.428)

-

The revolt of Francisco Hernández Girón against the Crown (p.430)

-

The rebel forces of Francisco Hernández Girón defeat the king’s soldiers at the battle of Chuquinga. (p.432)

-

Guaman Poma’s father, Don Martín Guaman Malqui de Ayala, leads a successful offensive on behalf of the Crown against the traitorous Francisco Hernández Girón and his men. (p.434)

-

Francisco Hernández Girón is taken prisoner by Apo Alanya, Chuqui Llanqui, and their soldiers, ending the rebellion against the king. (p.436)

-

20. The chapter of “good government” (438-490)

-

Don Antonio de Mendoza, the second viceroy of Peru (p.438)

-

Don Andrés Hurtado de Mendoza, Marquis of Cañete, the third viceroy of Peru (p.440)

-

Viceroy Don Andrés Hurtado de Mendoza receives Sayri Tupac Inka, King of Peru, and honors him in Lima. (p.442)

-

The Archbishop Juan Solano marries Sayri Tupac Inka and the Inka queen Doña Beatriz, quya. (p.444)

-

Don Francisco de Toledo, the fourth (actually, fifth) viceroy of Peru (p.446)

-

Captain Martín García de Loyola escorts the captured Tupac Amaru Inka to Cuzco. (p.451)

-

The execution of Tupac Amaru Inka by order of the Viceroy Toledo, as distraught Andean nobles lament the killing of their innocent lord (p.453)

-

Don Francisco de Toledo dies in Castile, after being refused an audience with Philip II. (p.460)

-

Martín Arbieto and Don Tomás Tupac Inka Yupanqui in the conquest of the Antisuyus and the Chunchos (p.462)

-

Don Martín Enríquez de Almanza, the fifth (actually, sixth) viceroy of Peru (p.464)

-

Don Fernando Torres y Portugal, Count of Villar, the sixth (actually, seventh) viceroy of Peru (p.466)

-

Don García Hurtado de Mendoza, the seventh (actually, eighth) viceroy of Peru (p.468)

-

Don Luis de Velasco, the eighth (actually, ninth) viceroy of Peru (p.470)

-

Don Carlos Monterrey (actually, Gaspar de Zúñiga y Acevedo, Count of Monterrey), the ninth (actually, tenth) viceroy of Peru (p.472)

-

Don Juan de Mendoza y Luna, Marquis of Montesclaros, the tenth (actually, eleventh) viceroy of Peru (p.474)

-

The archbishop of Lima, assisted by a sacristan (p.476)

-

The religious orders of this kingdom, “devout and obedient servants of God” (p.478)

-

The Inquisitor of the Holy Office of this kingdom and his chief assistant (p.480)

-

The rector general of the Society of Jesus with two Jesuit priests, “a very obedient religious order in Lima and throughout the world” (p.482)

-

One of the many saintly hermits of this kingdom, John the Sinner, with a native follower who says, “I respect you, holy man.” (p.484)

-

A chief abbess and an obedient nun, “saintly servants of God in this kingdom” (p.486)

-

The royal high court of Lima: president, judges, magistrates, crown attorney, and chief law enforcement official of this kingdom (p.488)

-

(491-560)

21. The chapter of colonial Indian administration (491-560)

-

The royal administrator (corregidor) and his secretary (p.492)

-

The royal administrator argues over money with a trustee of Indian land and labor (encomendero). (p.495)

-

Don Cristóbal de León, disciple and ally of “the author Ayala,” imprisoned by the royal administrator for defending the natives of the province. “I will hang you, vile Indian!” threatens the administrator. “For my people I will suffer in these stocks,” Don Cristóbal replies. (p.498)

-

A royal administrator sleeps peacefully beside his wife, while Don Cristóbal de León serves punishment for defending his people. (p.500)

-

The royal administrator orders an African slave to flog an Indian magistrate for collecting a tribute that falls two eggs short. (p.503) (See also p. 810.)

-

The royal administrator and his lieutenant make their nightly rounds. (p.507)

-

The royal administrator and his low-status dinner guests: the mestizo, the mulatto, and the tributary Indian. (p.509) (See also p. 617.)

-

The royal administrator Gregorio Lopes de Puga, man of learning, faithful servant of God and the poor (p.512)

-

The royal coat of arms that should be posted by the administrators on the doors of the municipal council: “Fear God, be just, and shun all evil and danger.” (p.515)

-

The placard that crown administrators should affix to the entrance of all royal inns: “Christians, fear God and the law. Eschew arrogance that you may avoid punishment.” (p.517)

-

A provincial judge and his native lieutenant after the hunt. “That’s for me,” says the judge. “Here you are, sir,” responds the assistant. (p.520)

-

A judge on judicial assignment demands: “Hand over the blanket, wretched Indian!” The Indian replies: “Don’t take it from me, sir!” (p.523)

-

The royal administrator’s notary receives a payoff from a tributary Indian. (p.525)

-

The administrator of the royal mines punishes the native lords with great cruelty. (p.529)

-

A judge, sent by an administrator of the royal mines, robs a native lord. (p.533)

-

A mine labor captain “rents” a native laborer to replace one of his own who has fallen ill from mercury poisoning. (p.535)

-

The royal overseer beats his native porter. (p.538)

-

A Spanish traveler mistreats his native carrier. (p.541)

-

The itinerant Spaniard orders his native porter: “Walk, Indian dog!” (p.545)

-

The exaggerated size and stature of Spanish men and women, “great gluttons” (p.548)

-

The arrogant creole (or mestizo or mulatto) assaults a native villager. (p.552)

-

The arrogant creole (or mestizo or mulatto) woman, “enemy of the poor Indians” (p.554)

-

Castilian-born Spaniards, well-instructed and honorable Christians (p.556)

-

“May the holy Catholic faith and the kingdom of Castile represented by this royal coat of arms reign in this kingdom and all the world.” (p.558)

-

22. The chapter of the trustees of Indians (encomenderos) (561-573)

-

23. The chapter of the parish priests (574-688)

-

The parish priest receives the blessings of St. Peter and St. Paul. (p.575)

-

The parish priest threatens the native weaver who works at his command. (p.578)

-

The parish priest administers civil justice with no authorization whatsoever to do so. (p.581)

-

Priests swapping parish assignments to take vengeance on their Indian parishioners (p.584)

-

The forced marriage of native parishioners by a parish priest (p.587)

-

“Bad confession”: a priest abuses his pregnant parishioner during confession. (p.590)

-

The parish priest’s fantasy: being an “absolute lord,” dressed in the finest silk (p.593)

-

Executioner: the cruel parish priest metes out punishment indiscriminately. (p.596)

-

At the age of five, native boys are brought to the parish, where they receive religious instruction and suffer cruel punishments. (p.599)

-

Don Juan Pilcone, local native authority, or kuraka kamachikuq, files a written complaint against the royal administrator with the help of the parish priest. (p.602)

-

A parish priest misuses doctrine as a weapon to punish a native parishioner for denouncing him to civil authorities: “Recite the doctrine, Indian troublemaker! Right now!” (p.605)

-

A native parishioner is beaten to death for defending unmarried Andean women and maidens from the lascivious priest. (p.608)

-

The parish priest and royal administrator at the gaming table (p.610)

-

The irascible parish priest raises the sword against a poor Spanish soldier. (p.614)

-

The parish priest and his thievish accomplices at the dinner table: common Indians, mestizos, and mulattoes. (p.617) (See also p. 509.)

-

The mestizo offspring of parish priests being taken away to Lima (p.620)

-

The priest's Quechua sermon brings sleep to some parishioners, the dove of the Holy Spirit to all. (p.623)

-

The sacrament of baptism (p.627)

-

The sacrament of confession (p.629)

-

The sacrament of matrimony (p.631)

-

Holy work of mercy: the rites of Christian burial (p.633)

-

The priest, fearing written accusations against him, seeks to confiscate all writing instruments in his new parish: “I'm not looking for notaries; tomorrow I'll be on my way.” (p.636)

-

The exemplary Christian priest celebrates daily mass with extreme devotion, and does not meddle with the law, commerce, or unmarried women. (p.639)

-

The vicar general protects the poor Indian with charity and justice. (p.641)

-

A Franciscan friar serving the poor through charity: “Eat this bread, poor fellow.” (p.643)

-

A hermit priest kneels to receive alms for the poor. (p.645)

-

The saintly nun of the convent accepting alms (p.647)

-

Jesuit fathers, “holy men throughout the world, who give all they own to the poor of this kingdom.” (p.649)

-

Holy work of charity: hermit priests, Franciscans, and Jesuits alike must do good works and charity for the poor and infirm of this kingdom. (p.651)

-

Holy feasts: St. James the Great, St. Mary, and St. Bartholomew before the holy cross of Carabuco (p.653)

-

Augustinian friars are quick to anger and abuse the Indians with little fear of God or the law. (p.657)

-

Wrathful, arrogant Dominicans force native women to weave for them. (p.659)

-

The Mercedarian friar Martín de Murúa abuses his parishioners and takes justice into his own hands. (p.661)

-

The sacristan calls parishioners to mass. (p.666)

-

An Indian woman, falsely accused of concubinage by the parish priest, presents her petition for justice to the native magistrate. (p.668)

-

The bishop's coat of arms (p.672)

-

The native assistants of the parish: the chorister, the church assistant, and the sacristan. (p.675)

-

The sacristan rings the bells to call the parishoners to mass and prayer. (p.678)

-

The church choir performs the Salve Regina. (p.680)

-

The chief attendant of the church, confraternities, and hospitals of this kingdom (p.682)

-

The cruel choir and school masters should teach their students to read and write, so that they become good Christians. (p.684)

-

Native artisans create religious images to serve God and the church. (p.687)

-

24. The chapter of the church inspectors (689-716)

-

The church inspector Cristóbal de Albornoz, with the help of his native assistant, administers punishment during an extirpation of idolatries campaign. (p.689)

-

The parish priest kneels obediently to greet the arriving church inspector. (p.692)

-

The church inspector Juan López de Quintanilla, friend of the poor and honest judge (p.695)

-

The inspector general of this kingdom, sent to Indies by the pope in Rome (p.698)

-

Six ungodly animals feared by the poor Indians of this kingdom: the royal administrator, a serpent; the itinerant Spaniard, a tiger; the encomendero, a lion; the parish priest, a fox; the notary, a cat; and the native lord, a rodent. (p.708)

-

Bishop Sebastián de Mendoza of Cuzco (actually, Fernando González de Mendoza), good Christian, lover of justice, and friend of the poor Indians and native lords of this kingdom (p.710)

-

A cardinal, ranking second to the pope, should oversee the church of the Indies. (p.713)

-

25. The chapter of the black Africans (717-725)

-

-

-

28. The chapter of the princes, native lords, and other hereditary Andean ranks (752-805)

-

Don Melchor Carlos Inka, native prince of this kingdom, who receives from the Spanish king the title of the Order of Santiago (p.753)

-

Guaman Chaua, qhapaq apu, powerful lord of the Yarovilca dynasty of Allauca Huánuco, from which “the author Ayala” claims descent and to whose descendants the Spanish king grants favors (p.755)

-

Quicia Uillca, apu, native lord of the Yauyo lineage that enjoys the favor of the emperor (p.757)

-

Paytan Anolla, Lucana, waranqa kuraka, native lord who administers one thousand native tributaries on behalf of the crown (p.759)

-

Cones Paniura, Taypi Aymara, pisqa pachaka kamachikuq, the chief overseer who administers five hundred tributary Indians (p.761)

-

Chuqui Llanqui, Xauxa Guanca, pisqa chunka kamachikuq, administrator of fifty native tributaries (p.763)

-

Grauiel Cacyamarca of the province of Andamarca, pachaka kamachikuq, administrator of one hundred native tributaries (p.765)

-

Chiara, of the pueblo of Muchuca, chunka kamachikuq, administrator of ten native tributaries (p.767)

-

Poma, of the pueblo of Chipao, of Allauca Huánuco lineage, mitmaq, descendant of Inka-era immigrants, pisqa kamachikuq, administrator of five native tributaries (p.769)

-

Qhapaq apu mama, wives of powerful lords: Poma Valca and Juana Curi Ocllo, quya, principal wife and queen of Peru (p.771)

-

Kuraka warmi, wives of kuraka, waranqa, and pisqa pachaka; Doña Juana Guaman Chisque, ñusta, princess of the kingdom of the Indies (p.773)

-

Exemplary Christians: A local Andean lord, seated on an usnu, or Inka ceremonial seat, reads to his wife. (p.775)

-

An Andean noble of second highest rank, in the service of the royal administrator, demands tributary laborers of the native overseer whom he meets on the road. (p.778)

-

The waranqa kuraka, administrator of one thousand tributary Indians, should serve the royal administrator by collecting tribute and supervising the native workforce. (p.781)

-

An upstanding native lord drafts a grievance on behalf of an Andean commoner. (p.784)

-

Don Juan Capcha, tributary Indian, great drunkard, and enemy of all Christians (p.790)

-

The native lord Don Carlos Catura, served by his son, spends the tribute he owes to the encomendero on wine, gambling, and prostitutes. (p.794)

-

The sons of native lords should dance before the Holy Sacrament during liturgical feasts. (p.797)

-

The native lord as well as the native tributary should be easily recognized by the clothes they wear. (p.800)

-

A native lord instructs a dutiful tributary to offer his goods to the royal administrator. “Lord administrator, I have come to offer you these things,” says the tributary. “Why don’t you bring me instead hens, capons, and llamas?” the administrator demands. (p.804)

-

29. The chapter of local native administrators of this kingdom (806-833)

-

The chief local magistrate, or t’uqrikuq, of the municipal council in this kingdom (p.806)

-

The local magistrate, or camiua, of the crown (p.808)

-

The royal administrator orders an African slave to flog an Indian magistrate for collecting a tribute that falls two eggs short. (p.810) (See also p. 503.)

-

The native administrator of resources, or surqukuq, with the book and knotted strings (khipu) he uses for accounting (p.814)

-

The chief native constable in this kingdom (p.816)

-

An old man, one of the native magistrates, town criers, or executioners of this kingdom (p.818)

-

The chief native attendant, or suyuyuq, who administers the community’s goods, should safekeep the depositories of the churches, confraternities, and hospitals of this kingdom. (p.820)

-

The royal administrator’s native lieutenant, or qhapaq apu suyuyuq, should safeguard the community depository. (p.822)

-

. Royal postal runners of this kingdom, hatun chaski and churu chaski, carry the king's dispatches. (p.825)

-

A native scribe of the municipal court, or qilqay kamayuq, drafts a will. (p.828)

-

30. The chapter of the Indians of this kingdom (834-922)

-

A native Christian couple kneeling in prayer before an image of the crucified Christ (p.835)

-

The devout prayers of an Andean woman summon the dove of the Holy Spirit. (p.837)

-

The Holy Trinity (p.839)

-

In a tribute to Santa María de Peña de Francia, Our Lady of Copacabana, and Our Lady of the Rosary, Guaman Poma depicts the Virgin Mary holding the baby Jesus, as St. Peter kneels before her in prayer. (p.841)

-

The saints of the church (p.843)

-

An angel from heaven comforts a soul in purgatory. (p.845)

-

All Christians should pray daily for their soul, their health, and for all the good in this world. (p.847)

-

Indians must learn to baptize their children in places where there is no priest: “I baptize you, Juan. In the name of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit. Amen.” (p.852)

-

Christians should give alms, especially in this kingdom of the Indies of Peru. (p.855)

-

A poor, crippled Andean woman, one of many in this kingdom who suffer mistreatment from priests, royal administrators, encomenderos, and native lords (p.858)

-

The traditional Andean laws of marriage established good order and “Christian” harmony among family members. (p.861)

-

The Andean hunter and gamekeeper, p’isqu kamayuq, an office that keeps men from vice (p.864)

-

All Indians should have a clock to order their daily lives of work and prayer. (p.867)

-

Creolized Indians spend their time singing and amusing themselves, rather than serving God. (p.870)

-

A native field laborer and his dog protect the crop from sparrows. (p.873)

-

Indians “speak with the devil” while practicing a traditional Andean drinking ritual. (p.876)

-

Native horticulturists tending their garden: “Chew this coca, sister.” (p.879)

-

Indian parents defend their daughter from the lascivious Spaniard. (p.882)

-

Indolent natives sleep throughout the morning, evading their duties in the fields. (p.885)

-

A young Andean man violates the Lord’s fourth commandment: “Die, old man!” shouts the son. “For God’s sake, don’t beat your father!” replies the elderly man. (p.888)

-

The native administrator confiscates an elderly Andean’s llama: “Hand over the tribute, old man,” he orders. “But I’m not subject to tribute. My fields, my home, and my llama were left to me by my father in his will,” the man answers. (p.891)

-

Native Andeans sacrifice a llama according to the ancient laws of idolatry. (p.894)

-

The native Andean astrologer, who studies the sun, the moon, and all other heavenly bodies in order to know when to plant the fields (p.897)

-

The native administrator demands tribute from an elderly Andean woman: “Hand over the tribute, old lady!” he commands. “What tribute could I possibly give you? I am an old woman and very poor,” she replies. (p.900)

-

31. The chapter of religious and moral considerations (923-973)

-

God, the creator of heaven and earth (p.924) (See also p. 12.)

-

Indians performing charitable works for the poor and infirm of this kingdom (p.927)

-

A Christian kneels before his lord, following the example of Cato of Rome and with the obedience characteristic of Christians during the early years of the conquest. (p.930)

-

The Andean confraternity of twenty-four, a model of good conduct and Christianity (p.933)

-

The fearless royal administrators and priests mistreat the poor Indians of this kingdom. (p.936)

-

How the Spaniards abuse their African slaves (p.939)

-

One of the many thieves who prosper in this kingdom. “You will rob well. I’m going to help you,” the devil promises. “Here are one hundred silver coins,” responds the thief. (p.942)

-

The Virgin Mary, kneeling alongside the saints of the church, prays to her son Jesus Christ. (p.946)

-

The crucified Christ, “who died for the world and for all sinners, the sons and daughters of Adam and Eve.” (p.949)

-

The city of heaven, reserved for those who keep God’s word (p.952)

-

The city of hell, where fearless sinners are punished (p.955)

-

32. The chapter of Guaman Poma’s dialogue with the king (974-999)

-

33. The chapter of this kingdom and its cities and towns (1000-1087)

-

Mapa Mundi of the Indies of Peru, showing the quatripartite division of the Inka empire of Tawantinsuyu (pp. 1001-1002)

-

The city of Santa Fe de Bogotá (p.1005)

-

The city of Popayán (p.1007)

-

The city of Atres (p.1009)

-

The city of Quito, seat of the royal high court (p.1011)

-

The town of Riobamba (p.1013)

-

The city of Cuenca (p.1015)

-

The city of Loja (p.1017)

-

The city of Cajamarca, “city of Atahualpa Inka” (p.1019)

-

The town of Conchucos, silver mines (p.1021)

-

The town of Paita (p.1023)

-

The city of Trujillo (p.1025)

-

The town of Zaña (p.1027)

-

The town of Puerto Viejo (p.1029)

-

The city of Guayaquil (p.1031)

-

The city of Cartagena (p.1033)

-

The city of Panamá, royal high court and bishopric of the church (p.1035)

-

The city of Huánuco, “falcon and royal lion, waman puma” (p.1037)

-

The City of the Kings of Lima, royal high court, principal city of the kingdom of the Indies, residence of the viceroy, and archbishopric of the church (p.1039)

-

The town of Callao, port of Lima (p.1041)

-

The town of Camaná (p.1043)

-

The town of Cañete (p.1045)

-

The fishing town of Pisco (p.1047)

-

The town of Ica, the best wine region of the kingdom (p.1049)

-

The town of La Nasca, wine region (p.1051)

-

The town of Castrovirreina, silver mines (p.1053)

-

The town of Oropesa de Huancavelica, mercury mines where Indians endure great hardships (p.1055)

-

The city of Huamanga, “founded by the qhapaq apu Don Martín de Ayala” (p.1057)

-

The city of Cuzco, principal city and royal court of the twelve Inka kings of this realm, and bishopric of the church (p.1059)

-

The city of Arequipa, covered in ash following the eruption of its volcano (p.1061)

-

The town of Arica, covered in volcanic ash (p.1063)

-

The rich imperial town of Potosí, where the crown and the church are defended by the Inka and his four kings (p.1065)

-

The coat of arms of Potosí, “Ego fulcio collumnas eius.” (p.1066)

-

The city of Chuquisaca, royal high court and bishopric (p.1069)

-

The city of Chuquiyabo (p.1071)

-

The town of Misqui (p.1073)

-

The city of Santiago de Chile, bishopric (p.1075)

-

The native pukara and the Christian fortress of Santa Cruz de Chile, the scene of battles between Spanish Christians and the native infidels of Chile (p.1077)

-

The city of Tucumán, bishopric (p.1079)

-

The city of Paraguay, bishopric (p.1081)

-

-

35. The chapter of the inns, or tanpu, on the royal road (1092-1103)

-

36. The chapter of the author’s journey to Lima (1104-1139)

-

37. The chapter of the months of the year (1140-1178) (See also ch. 11.)

[Chapter 38 has no drawings.]

-

January: Maize, time of rain and digging up the earth; Qhapaq Raymi Killa, month of the greatest feast (p.1142)

-

February: Time of watching the maize at night; Pawqar Waray Killa, the month of donning loincloths (p.1145)

-

March: Time of chasing parrots from the maize fields; Pacha Puquy Killa, month of the maturation of the soil (p.1148)

-

April: Maturation of the maize, time of protecting it from thieves; Inka Raymi Killa, month of the Inka’s feast (p.1151)

-

May: Time of reaping, of gathering the maize; Aymuray Killa, month of harvest (p.1154)

-

June: Time of digging up the potatoes; Hawkay Kuski Killa, month of rest after the harvest (p.1157)

-

July: Month of taking away the maize and potatoes of the harvest; Chakra Qunakuy Killa, month of the distribution of lands (p.1160)

-

August: Triumphal songs, time of turning the soil; Yapuy Killa, month of turning the soil (p.1163)

-

September: Cycle of sowing maize; Quya Raymi Killa, month of the feast of the queen, or quya (p.1166)

-

October: Time of watching over the fields in this kingdom; Uma Raymi Killa, month of the feast of origins (p.1169)

-

November: Time of watering the maize, of scarcity of water, time of heat; Aya Marq’ay Killa, month of carrying the dead (p.1172)

-

December: Time of planting potatoes and uqa, tubers; Qhapaq Inti Raymi Killa, month of the festivity of the lord sun (p.1175)

-

39. Conclusion of the Nueva corónica y buen gobierno (1188-1189)

|

|

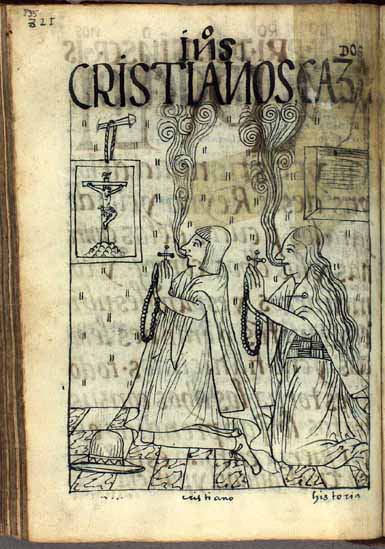

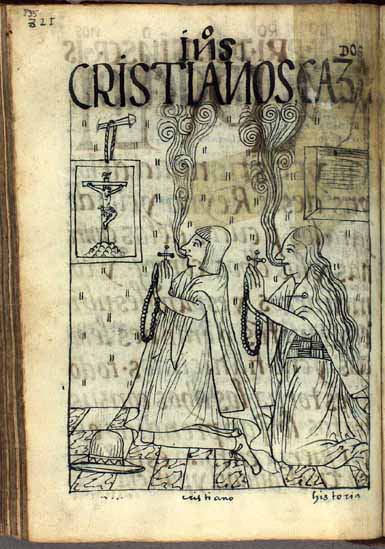

Drawing 308.

A native Christian couple kneeling in prayer before an image of the crucified Christ

821 [8351]

CRISTIANOS CAZADOS

/ cristiano /

IN[DI]OS

Véase la nota, p. 834.

|